How to Get an Entire Organization to Try Pair Programming: A Bottom-Up Experiment

Developers at SpareBank 1 Utvikling, together with researchers from SINTEF, have developed an effective model for helping teams establish pair programming as a lasting practice.

Cross-country skiing and an idea

A few years ago, while skiing in Oslo-Marka, I had an idea.

What if we simply asked teams to try pair programming for three weeks as an experiment? It should be simple, fun, low-threshold, and not interfere with planned activities. It would come from the bottom up. No mandates from management, no “rollout.” You should be able to see results quickly. Developers usually like that.

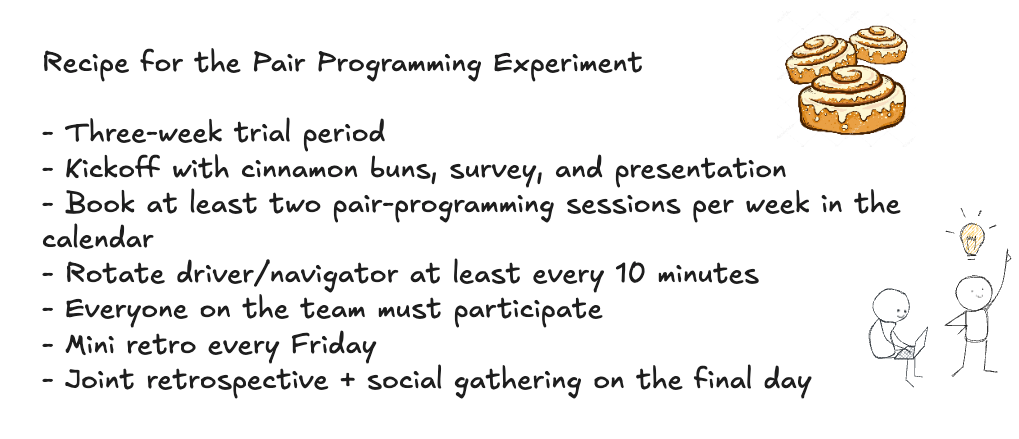

The experiments had only two requirements:

- Developers book two pair-programming sessions per week (in their calendars) during the trial period

- Switch driver/navigator in the pairs at least every 10 minutes

It turned out to be a success.

Three years later, researchers from SINTEF published a research paper in the well-respected journal Journal of Systems and Software on how the pair-programming experiments proved to be a highly effective way of establishing pair programming as a practice in an organization.

SpareBank 1 Utvikling and Team PM Account

Just to give a bit of context about who we are.

We work at SpareBank 1 Utvikling, a software company owned by an alliance of Norwegian savings banks under the SpareBank 1 brand. It has around 600 employees and builds the group’s digital banking platform.

For the past four years, we’ve worked in Team PM Account, which is responsible for the retail banking account domain. The APIs we maintain handle around 80 million requests per day from 1.3 million unique users and are critical to the digital bank functioning properly. If we get something wrong, it can easily make front-page news.

Our team consists of four developers and a hybrid team lead/product manager. We practice TDD, mob/pair on everything we do, and deploy to production multiple times per hour. We don’t spend time on pull requests (PRs), and we test exclusively in production. (See our discussion with Dave Farley on pull requests.)

Over several years, we’ve shown that with the way we work, we can deliver high quality quickly and with low risk, even on the most critical parts of the digital bank’s codebase. We love the way we work, and our main goal is to help as many people as possible have a workday like ours.

Through the experiments, we wanted to spread these practices to as many teams as possible.

The Pair Programming Experiment Recipe

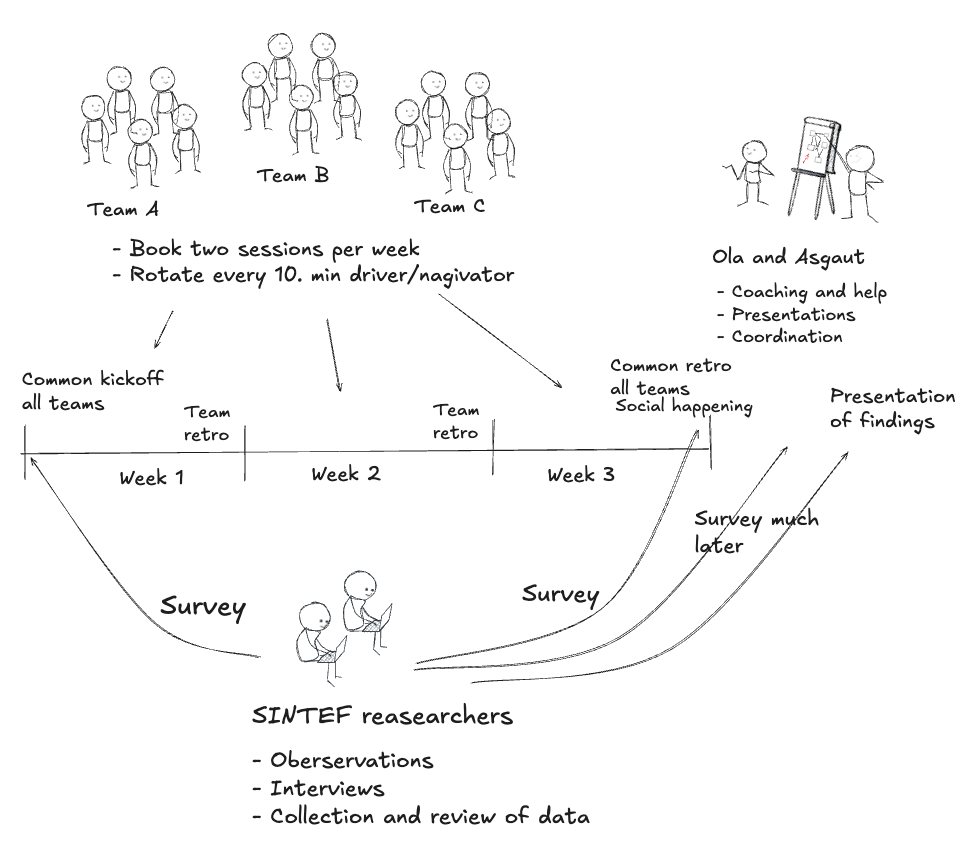

Together with SINTEF, Ola Hast and I ran the experiments. We ended up with the following recipe when a product area wanted to run the experiment:

Ola and I stayed in continuous dialogue with developers and team leads throughout the period. After each weekly retro, we reviewed the feedback and suggested adjustments for what teams could try next. On the final day of the experiment, SINTEF facilitated a joint retrospective for all the teams involved. Then we wrapped up by doing something social together.

SINTEF conducted surveys before and after the experiment, as well as a few months after it had concluded. They also made observations and conducted interviews. They then compiled the responses and analyzed the data as part of their research.

This wasn’t very hard to do. It required little from us and little from the participants. And it turned out to deliver very high value, very quickly.

Findings from the SINTEF research

The research conducted by SINTEF has given us a solid foundation for summarizing how the experiments have impacted the organization.

This is what the research says about the benefits of pair programming and the experiments:

- Reduces waste and waiting, and shifts time toward value-creating work

- Builds psychological safety

- Spreads competence and knowledge of the solutions within the team

- Participants want to pair program more

- A good way to introduce a new practice

- Builds culture within a product area

- Leads to more cross-functional collaboration (e.g., designer–developer, tester–developer)

- Provides more strategies for increasing focus (e.g., frequent driver/navigator rotation)

- Especially useful when tasks are complex

- Many appreciate the social aspect and experience it as contributing to well-being

- Provides strong support for onboarding new hires

Five product areas and 21 teams over three years

Already in the first experiment, we saw positive changes in the teams. Over time, we moved from calling them “pair programming experiments” to “pair working experiments.” We found that all roles in the teams could take part, including testers, designers, leaders, and others. With each experiment, we iterated and learned, so we could make the next one better.

We worked with one product area at a time, each typically consisting of several teams. After three years, we had run experiments across five areas with a total of 21 teams, and more teams are lining up for new experiments.

Frequent rotation is crucial for pair programming to work

Three hundred years ago, Benjamin Franklin said: “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.”

If one developer (typically the more experienced one) sits and codes for two hours while another developer watches, that’s not pair programming. This is a classic misunderstanding, and we saw it again and again in the experiments.

The person observing gradually loses motivation, struggles to keep up, and learns less. People need to be actively involved.

Regardless of whether someone is junior or senior, we follow the same setup: the driver and navigator rotate at least every 10 minutes. We use a timer, and when the time is up, we switch quickly, either physically at the keyboard or via git push/pull. The same applies when we work remotely.

SINTEF observed developers during the experiments and saw a significant change when pairs rotated frequently and consistently. People had better focus and flow, and both parties gained greater knowledge of and ownership over what they built.

It’s about doing

One thing SINTEF found particularly interesting was how the experiments helped introduce a new practice in the organization. It’s not enough to just hear that a practice is useful, people need to experience it firsthand. When team members experience for themselves how pair programming actually makes it easier to solve tasks, learn more, or improves well-being, the likelihood that they will continue with it increases significantly.

Because the experiments were low-threshold and tied to work the teams were already doing, they gave teams exactly this kind of valuable hands-on experience with the practice. SINTEF believes that similar experiments can also be used to introduce practices other than pair programming.

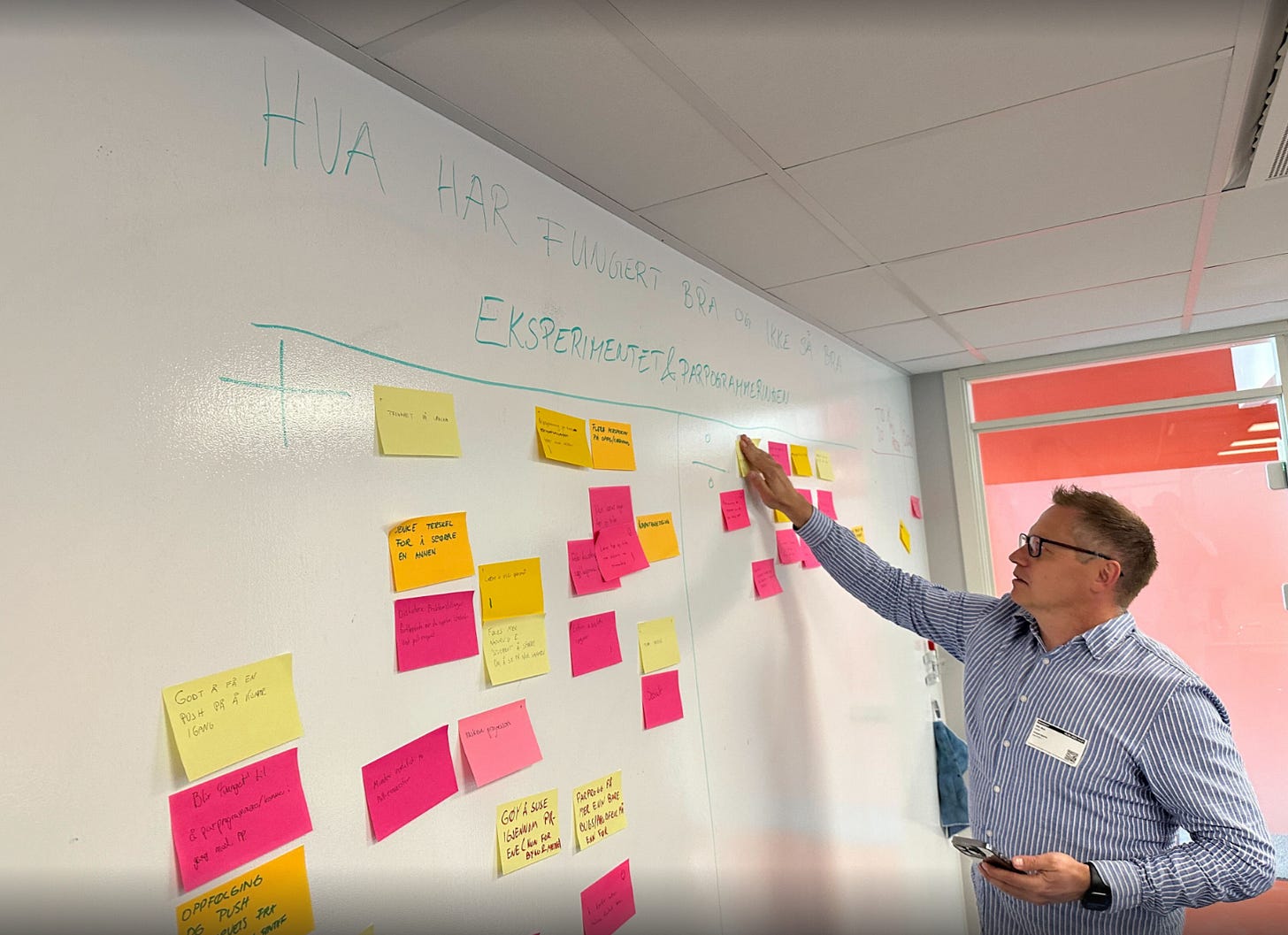

The experiments also surfaced other issues in the teams

The weekly retrospectives in the experiments helped surface challenges early, which in turn allowed us to coach more effectively.

Not all teams are used to such close collaboration. When we introduced this way of working, other issues also became much more visible, which gave the experiments additional value. For example:

- Some teams were dependent on individual “experts". People outside the team went straight to these individuals when problems arose, turning them into bottlenecks.

- Larger teams struggled to align on shared goals.

- Many didn’t know what to do once the pair-programming session they had booked was over.

- Teams struggled to form pairs because some people were tied up with other work that was considered “not suitable for pair programming.”

Big teams struggle with shared goals

In one of the experiments, the team consisted of 15–20 people. At the start of the week, they were asked to give a confidence vote on how likely they thought the team was to reach its goals. Everyone gave completely different answers. This was because each person was only thinking about what they personally were going to work on. The researchers at SINTEF pointed out that this isn’t really a team, but rather a group of people working without shared goals.

Based on this, we gave the following advice:

- Tasks in the team should not be assigned to individuals, but owned by the team

- Fewer tasks per week, and all work should be done in pairs

- All types of tasks, big and small, are suitable for pair work, not just pure coding tasks

- SINTEF’s research shows that small teams work best. Split into smaller teams or sub-teams

- Create small changes that can go to production quickly. This also makes it easier to rotate who works together in the team, instead of having someone tied to a large task for a long period

- Questions directed at “experts” should instead be addressed to the whole team. Anyone can respond, with support from the experts if needed

Pair programming isn’t actually the goal

Just to be clear, pair programming is not a goal in itself. The goal is continuous delivery with high quality.

This is what we wanted participants to experience through the experiments.

If a team of four were to work individually and deploy to production several times per hour, they would interrupt each other so much with reviews that it would immediately fall apart. The consequence is that they end up building larger batches, quality goes down, and risk goes up. When you do pair programming, code reviews effectively happen during development.

Continuous delivery at this pace simply isn’t possible without pair programming. We talked about this at QCon London 2025.

Pair programming leads to positive outcomes such as reduced waste, less rework, higher quality, better knowledge sharing, fewer bugs, and improved collaboration within the team. Combined with TDD, the code design becomes significantly better because everything is discussed continuously, design decisions are made early, and the feedback loop is much faster.

All of this results in continuous, high-quality learning, which is critical for quality. This is the scientific approach to software development that Dave Farley describes in his book Modern Software Engineering.

Driving culture change

What we like most of all is that the experiments have contributed to “developer joy.” When Ola and I hear about less waiting time in teams, better team health, increased psychological safety, and that people are doing better at work, that’s exactly the impact we’re hoping for.

Pair programming across teams

At SpareBank 1 Utvikling, we cultivate learning. Since 2018, we’ve had one full day every week dedicated purely to professional development. On that day, we work exclusively on learning. It’s the best day of the week.

The experiments have helped developers become more comfortable with pair programming, which makes them more likely to pair up with developers from other teams on learning day. This has also significantly strengthened team mobility, both for onboarding and offboarding.

Summary

The pair programming experiments demonstrate, through both practice and research, how new ways of working can be introduced in large organizations. By running voluntary, time-boxed, research-backed experiments, we achieved real behavior change, not just agreement that pair programming is a good idea.

- Real change comes from experiments, not mandates: Small, voluntary, time-boxed experiments lead to actual adoption

- Low threshold, high impact: A simple structure (three weeks, two rules) was enough to trigger lasting change

- Frequent driver/navigator rotation: Rotating at least every 10 minutes had a strong impact

- Pair programming is a means, not the goal: The value lies in continuous delivery with high quality, low risk, and fast learning

- Organizational learning > technical practice: The experiments surfaced structural issues in teams, collaboration, ownership, and shared goals, enabling improvement

- A scalable model for change: The approach is transferable to other practices

- Fun and low-threshold: All types of work can be done together, making it possible for roles beyond developers to participate

Read on in How to Get an Entire Organization to Try Pair Programming: Team shadowing (coming soon)